In the annals of history, few figures stand as tall and tragically luminous as Hypatia of Alexandria. A mathematician, astronomer, and philosopher, she was a beacon of intellect in a world ruled by social constraints, religious conflict, and gender inequality. Living in the vibrant yet volatile city of Alexandria during the late 4th and early 5th centuries CE, Hypatia broke barriers in fields dominated by men and left an enduring legacy as a symbol of reason, wisdom, and courage.

This blog article explores the life, achievements, and untimely death of Hypatia, highlighting her contributions to science and philosophy, and why her story continues to inspire today.

The Making of a Mind: Hypatia’s Early Life

Born around 355 CE in Alexandria, Egypt, Hypatia was the daughter of Theon of Alexandria, a prominent mathematician, astronomer, and philosopher. Unlike most women of her era, who were largely excluded from formal education and intellectual life, Hypatia benefited from her father’s enlightened approach to parenting. Theon envisioned raising a “perfect” human being—physically, intellectually, and morally—and Hypatia was his prodigy.

Under Theon’s guidance, Hypatia mastered mathematics, astronomy, rhetoric, and philosophy. More than just a scholar, she became an educator and a public intellectual, drawing students from across the Mediterranean to learn at her feet.

Contributions to Mathematics and Astronomy

Though none of Hypatia’s original works survive, historical records attribute to her several commentaries and instructional texts, most of which aimed to preserve and clarify ancient knowledge. Her intellectual efforts were largely focused on editing and expanding upon classical Greek works.

Key Contributions:

Worked on a new edition of Euclid’s Elements, likely in collaboration with her father. This version became the standard reference for centuries.

Assisted in writing an eleven-part commentary on Ptolemy’s Almagest, a foundational astronomical treatise.

Authored (now lost) commentaries on Diophantus’s Arithmetica (a seminal work in algebra) and Apollonius’s Conics (on geometry).

Created an astronomical table and possibly modified an existing one to enhance its accuracy.

Advised on the design and use of scientific instruments like the astrolabe (used for navigation and timekeeping) and the hydroscope (an ancient water-measuring device).

Though she may not have introduced original mathematical theorems, Hypatia was an exceptional compiler, editor, and teacher who ensured the survival and continued relevance of classical mathematical thought.

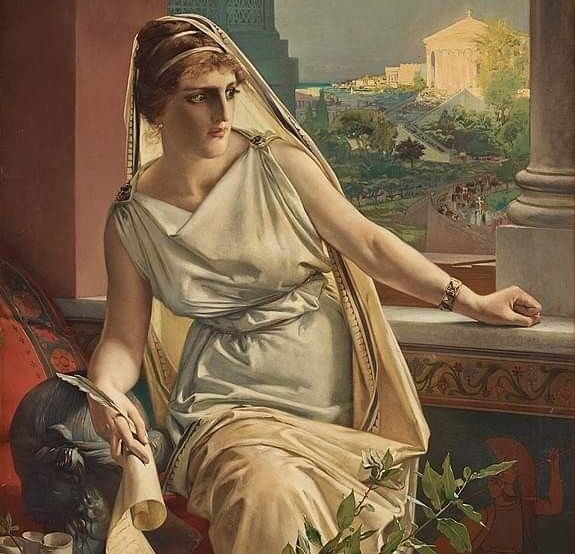

A Philosopher in Public

Hypatia wasn’t just a scientist—she was also a Neoplatonist philosopher, a follower of a school of thought founded by Plotinus and developed further by Iamblichus. Neoplatonism emphasized the idea of a single, perfect, and transcendent source—”The One”—from which all reality emanates.

Hypatia taught that human beings could approach this ultimate reality through philosophical reasoning, abstraction, and the pursuit of knowledge. She saw mathematics not just as a technical discipline, but as a means to spiritual and intellectual enlightenment. Her teachings were a synthesis of science, metaphysics, and ethics.

Her public lectures drew huge crowds, and she became one of the most respected thinkers in Alexandria—a city then known as a hub of learning but also torn by sectarian conflict.

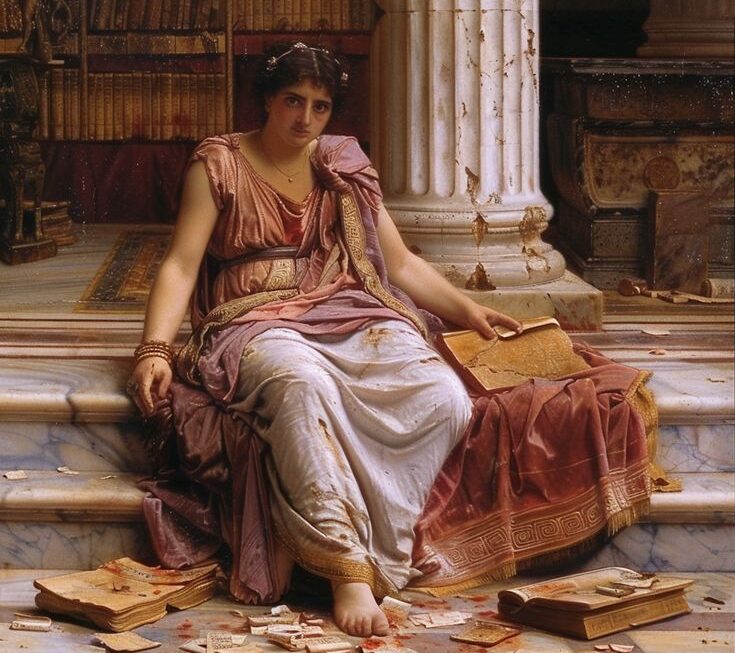

A Woman Ahead of Her Time

In an age when women were rarely educated—let alone encouraged to speak in public or contribute to intellectual debates—Hypatia was a remarkable exception. She headed the Platonist school of Alexandria around 400 CE, mentoring both male and female students. Some of her followers, such as Synesius of Cyrene, went on to become influential Christian bishops, demonstrating that Hypatia’s reputation transcended religious boundaries.

Synesius’s surviving letters to Hypatia reflect profound admiration for her intellect and moral character. He often sought her advice on philosophical matters and scientific tools, indicating the trust and respect she commanded among Alexandria’s elite.

Conflict and Tragedy

Despite her popularity, Hypatia lived during a time of intense political and religious instability. Alexandria was a melting pot of cultures and faiths—pagans, Jews, and a growing population of Christians. By the early 5th century, tensions between these groups had reached a boiling point.

In 412 CE, Cyril became the bishop (or patriarch) of Alexandria. His rise to power intensified hostilities between the Christian Church and the Roman administration, represented by Orestes, the city’s prefect. Hypatia, being a prominent public figure and a close confidant of Orestes, was falsely accused of fueling this political rivalry and standing in the way of Christian dominance.

In 415 CE, while on her way to a public lecture, Hypatia was brutally murdered by a mob of Christian zealots. Some accounts describe the attackers as Nitrian monks, followers of Cyril, while others attribute the act to an angry Christian mob led by a man named Peter. She was dragged through the streets, stripped, and killed in an appallingly violent manner.

Though historians continue to debate the extent of Cyril’s involvement, the event was undeniably linked to the era’s religious extremism and intolerance. Hypatia’s death marked not only a tragic loss for science and philosophy but also a symbolic turning point in the struggle between reason and dogma.

Hypatia’s Enduring Legacy

Hypatia’s life and death left a deep imprint on both historical scholarship and modern culture.

Her impact includes:

Symbol of intellectual freedom: Hypatia is celebrated today as a martyr for science, reason, and the right to think freely.

Feminist icon: As one of the earliest known female intellectuals, she has become a powerful figure in the history of women’s rights.

Preservation of knowledge: Her editorial work helped ensure the survival of key ancient texts that laid the foundation for later advances in mathematics and astronomy.

Literary and artistic inspiration: Hypatia has inspired novels, plays, films, and philosophical discussions. Notably, Charles Kingsley’s 1853 novel Hypatia, or New Foes with an Old Face and the 2009 film Agora brought renewed attention to her life.

Conclusion: A Legacy That Lives On

Hypatia of Alexandria lived in a world that was not ready for her brilliance, independence, or vision. Yet she persisted, becoming a trailblazer in mathematics, science, and philosophy during one of history’s most chaotic periods. Her life was a testament to the power of knowledge over ignorance, of dialogue over division, and of truth over tyranny.

Though her works were lost to time, her spirit endures in every classroom, observatory, and public forum where ideas are shared freely and without fear. Hypatia’s story reminds us that intellectual courage and the pursuit of wisdom are always worth fighting for.